Lu Yu (733 – 804), styled himself Hongjian, also known as Ji and with the courtesy name of Jici. He was nicknamed Jinglingzi, Sangzhuweng, and Donggangzi. A native of Jingling in Fuzhou of the Tang Dynasty (present-day Tianmen, Hubei Province), he had a passion for tea all his life and was proficient in the art of tea. He was renowned worldwide for writing the world’s first monograph on tea – “The Classic of Tea”, and made outstanding contributions to the development of the tea industry in China and around the world. He was honored as the “Immortal of Tea”, praised as the “Sage of Tea”, and worshipped as the “God of Tea”. He was also good at poetry, though not many of his works have been passed down.

A Legendary Life

Lu Yu’s life was full of legends. He was originally an abandoned orphan. In the 23rd year of the Kaiyuan period of the Tang Dynasty (735 AD), when Lu Yu was three years old, he was picked up by Zen Master Zhiji, the abbot of Longgai Temple in Jingling, on the shore of the local West Lake. Master Zhiji used the “Book of Changes” to divine for the child’s name. He got the hexagram of “Jian”, and the divinatory words said: “The wild swan gradually approaches the land; its feathers can be used for ceremonies.” So, according to the divinatory words, he gave the child the surname “Lu”, named him “Yu”, and took “Hongjian” as his courtesy name. Lu Yu learned to read and write, recited Buddhist scriptures, and also learned how to make tea in the temple with the dim light of oil lamps and the sound of bells and Buddhist chants. However, he was unwilling to convert to Buddhism and become a monk. When he was nine years old, once Zen Master Zhiji asked him to copy scriptures and chant Buddha’s name, but he asked Master Zhiji: “Buddhist disciples have no brothers when alive and no descendants when dead. Confucianism says that among the three forms of unfilial conduct, having no descendants is the worst. Can monks be considered filial?” And he blatantly declared: “I will study the teachings of Confucius.” Master Zhiji was annoyed by his rebellious and disrespectful attitude towards his elders, so he used heavy and menial tasks to discipline him and force him to repent. He made Lu Yu “sweep the temple grounds, clean the monks’ toilets, trample in the mud and smear the walls, carry tiles to repair the houses, and herd one hundred and twenty hooves of cattle”. Lu Yu was not discouraged or subdued by this. Instead, his desire for knowledge became even stronger. Having no paper to practice writing, he used bamboo sticks to write on the backs of cattle. Once he accidentally got Zhang Heng’s “Ode to the Southern Capital”. Although he didn’t know the characters, he sat upright, unrolled the scroll, and mumbled the words. When Master Zhiji found out, fearing that he would be influenced by non-Buddhist classics and deviate from Buddhist teachings for a long time, he locked Lu Yu up in the temple, ordered him to cut down weeds, and also sent elders to supervise him.

When he was twelve years old, taking advantage of people’s inattention, he escaped from Longgai Temple and joined a troupe to learn acting and became an actor. Although he was not good-looking and had a stutter, he was humorous and witty and was very successful in playing clown roles. Later, he also compiled three volumes of joke books titled “Xue Tan”. In the fifth year of the Tianbao period of the Tang Dynasty (746 AD), Li Qiwu, the prefect of Jingling, saw Lu Yu’s outstanding performance during a gathering of local people and greatly appreciated his talent and ambition. Immediately, he presented him with books of poetry and wrote a letter recommending him to study with Master Zou, who lived in seclusion on Huomen Mountain. In the eleventh year of the Tianbao period (752 AD), Cui Guofu, the director of the Ministry of Rites, was demoted to be the assistant magistrate of Jingling. That year, Lu Yu bid farewell to Master Zou and went down the mountain. Cui and Lu got to know each other and often went on outings together, tasted tea, appraised water, discussed poetry, and exchanged views on literature. In the thirteenth year of the Tianbao period (754 AD), Lu Yu traveled to the Bashan and Xiachuan areas to investigate tea affairs. Before leaving, Cui Guofu gave him a white donkey, a black plow ox, and a letter written on the bark of a Chinese scholar tree. Along the way, whenever he came across a mountain, he would stop his horse to pick tea leaves, and when he encountered a spring, he would dismount to taste the water. There were so many things to see and so many people to visit that his pen was too busy to record everything, and he returned with his brocade bags full.

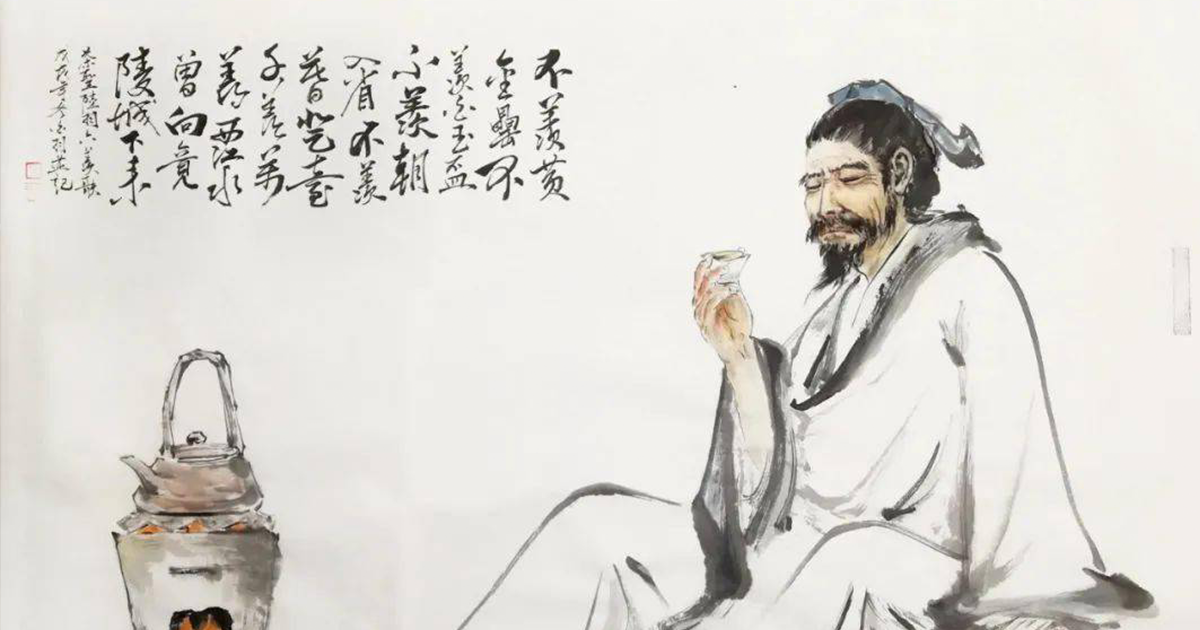

In the first year of the Qianyuan period of Emperor Suzong of the Tang Dynasty (758 AD), Lu Yu came to Shengzhou (present-day Nanjing, Jiangsu Province) and lived in Qixia Temple to study tea affairs. The next year, he lived in Danyang. In the first year of the Shangyuan period of the Tang Dynasty (760 AD), Lu Yu came from the foot of Qixia Mountain to the Tiaoxi River (present-day Wuxing, Zhejiang Province), lived in seclusion in the mountains, and shut himself up to write “The Classic of Tea”. During that period, he often wore a gauze scarf and short coarse clothes, put on rattan shoes, walked alone in the wild, went deep into farmers’ homes, picked tea leaves, searched for springs, evaluated tea, and tasted water. Sometimes he chanted scriptures and recited poems, beat the trees with his walking stick, played with flowing water, lingered hesitantly, and often didn’t return until it was dark and he was exhausted. People at that time called him the “Madman Jieyu of the Chu State” in modern times. Emperor Daizong of the Tang Dynasty once summoned and appointed Lu Yu as the Literature Attendant of the Crown Prince and later transferred him to be the Grand Libationer of the Taichang Temple, but he didn’t take up either position. Lu Yu despised the powerful and wealthy all his life, loved nature deeply, and adhered to justice. A poem by Lu Yu recorded in “The Complete Tang Poems” exactly reflects his character:

I don’t envy the golden wine vessels,

I don’t envy the white jade cups,

I don’t envy entering the court in the morning,

I don’t envy ascending the stage in the evening;

I envy the West River water thousands of times,

Which once flowed down to the city of Jingling.

“The Classic of Tea”

Lu Yu’s “The Classic of Tea” is a systematic summary of the scientific knowledge and practical experience related to tea before and during the Tang Dynasty. It was the crystallization of Lu Yu’s personal practice, unremitting efforts, obtaining first-hand information on tea production and processing, as well as extensively consulting numerous books and widely collecting the tea-picking and tea-making experiences of tea experts. Once “The Classic of Tea” came out, it was treasured and loved by people in successive dynasties, and they highly praised Lu Yu’s pioneering contributions to the tea industry. Chen Shidao of the Song Dynasty wrote a preface for “The Classic of Tea”: “The writing of books on tea started from Lu Yu. Its application in the world also began with Lu Yu. Lu Yu truly made great contributions to tea!”

Apart from comprehensively describing the distribution of tea-growing areas and evaluating the quality of tea in “The Classic of Tea”, Lu Yu was the first to discover many famous teas. For example, the Guzhu Zisun Tea in Changcheng (present-day Changxing County) in Zhejiang Province was rated as top-quality by Lu Yu and later listed as a tribute tea. The Yangxian Tea in Yixing County (present-day Yixing, Jiangsu Province) was directly recommended by Lu Yu to be presented as tribute. “The Record of the Reconstruction of the Tea House in Yixing County” records: “Li Xiyun, the imperial censor, was in charge of this region. When local people presented excellent tea, he invited guests to taste it. Lu Yu, a hermit, thought that the tea had a fragrant, sweet, and spicy flavor, which was superior to that of other places and could be recommended to the emperor. Li Xiyun followed his advice and began to present ten thousand taels of it. This was the origin.”

Legends about Lu Yu’s Tea Tasting and Water Appraisal

Many ancient books also recorded miraculous legends about Lu Yu’s tea tasting and water appraisal. Zhang Youxin of the Tang Dynasty described such an incident about Lu Yu in “The Record of Boiling Tea Water”: “During the reign of Emperor Daizong, Li Jiqing was the governor of Huzhou. When he arrived in Yangzhou (present-day Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province), he met Lu Yu, a recluse. Li had long been familiar with Lu’s reputation and was very happy to meet him. So they went to the prefecture together and moored at the Yangzi Post Station. When they were about to have a meal, Li said: ‘Mr. Lu is good at tea and is famous all over the world. Moreover, the water from Nanling in the south of the Yangtze River is extremely excellent. Today, with these two wonderful things meeting by chance once in a thousand years, how can we miss this opportunity!’ He ordered a cautious and reliable soldier to take a bottle and row a boat to go deep into Nanling to fetch water. Lu Yu sharpened his tools and waited. Soon the water was brought back. Lu Yu scooped up the water with a ladle and said: ‘It’s from the Yangtze River, but it’s not from Nanling. It seems to be water from the shore.’ The messenger said: ‘I rowed the boat deep into the water. Hundreds of people saw me. How dare I deceive you?’ Lu Yu didn’t say anything. Then he poured the water into a basin. When it was half full, Lu Yu suddenly stopped and scooped it up again with a ladle and said: ‘From this point on, it’s the water from Nanling!’ The messenger was greatly shocked and admitted his guilt, saying: ‘I fetched the water from Nanling to the shore, but the boat capsized and half of the water was spilled. I was afraid that there wasn’t enough, so I scooped up some water from the shore to make up for it. Sir, your judgment is truly divine. How dare I hide it?’ Li and dozens of his followers were all greatly astonished. Li then asked Lu Yu that since he could judge like this, he must be able to distinguish the quality of the water in all the places he had been to. Lu Yu said: ‘The water of the Chu State is the best, and the water of the Jin State is the worst.’ Li then took up a pen and wrote down the order as Lu Yu dictated.”

In the “Biography of Lu Yu” in the “Biographies” of “The New Book of Tang”, this incident was also recorded. But when it came to Li Jiqing summoning Lu Yu, “Lu Yu wore rustic clothes and brought his tea-making utensils and entered. Li Jiqing didn’t show him due courtesy. Lu Yu felt ashamed and wrote another book called ‘On Destroying Tea’.” The worship of Lu Yu as the “God of Tea” began in the late Tang Dynasty. Zhao of the Tang Dynasty, who once served as the prefect of Quzhou, had a grandfather who had a deep friendship with Lu Yu. He said in “Yinhua Lu”: “Lu Yu had a passion for tea and was the first to create the method of frying tea. Up to now, in the tea shops, people make pottery statues of him and place them among the tea-making utensils, believing that it’s good for tea and brings good profits.” Li Zhao of the Tang Dynasty wrote in “Guoshi Bu” that among the potters in Gong County, many made porcelain figurines named Lu Hongjian. If you bought dozens of tea utensils, you could get one Lu Hongjian. When the tea merchants didn’t sell tea well, they would pour tea on the figurines.

Other Works

Lu Yu was versatile. Besides “The Classic of Tea”, he also had quite a number of other works. According to “The Autobiography of Lu Wenxue” in “The Finest Blossoms in the Garden of Literature”, “After An Lushan’s rebellion in the Central Plains, I wrote the ‘Four Sad Poems’. When Liu Zhan invaded the Jianghuai region, I wrote the ‘Ode to the Unbright Sky’. Both were written to express my feelings at that time, with tears streaming down my face. I also wrote ‘The Covenant between the Monarch and the Minister’ in three volumes, ‘The Interpretation of the Origin’ in thirty volumes, ‘The Genealogy of the Four Surnames in Jiangxi’ in eight volumes, ‘The Records of People from the North and the South’ in ten volumes, ‘The Record of Officials in Wuxing’ in one volume, and ‘On Dream Interpretation’ in three volumes.” According to “The Gazetteer of Lin’an in the Xianchun Period”, when Lu Yu lived in Qiantang (present-day Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province), he wrote “The Records of Tianzhu and Lingyin Temples” and “The Records of Wulin Mountain”. Unfortunately, few of these works have been passed down.